A coordinate measuring machine, generally abbreviated as CMM or CMM machine, is a piece of industrial equipment that measures dimensional quantities of a physical object at the end of a manufacturing step. Historically, these measurements have been achieved with hand tools or optical comparators, but with increasing industrialisation, the need for automation of this labour-intensive task arose.

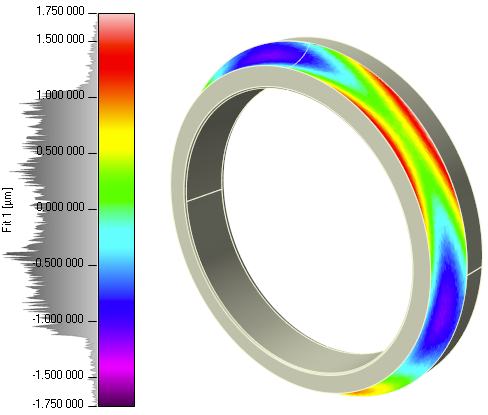

A coordinate measurement machine collects dimensional information from the component under measurement by probing its contour either with a touch probe or an optical sensor. The resulting point cloud is nowadays compared straight to a CAD model with deviations from design intent highlighted.

CAD model of a bearing with measured data of the bearing race overlaid.

Conventional, manual measurement using callipers is limited to simple measurements of distances. These measurements are time consuming and prone to operator errors. Even a very skilled inspector will eventually lose concentration and make a mistake in recording measured data. More sophisticated parts require more sophisticated measurements with tighter tolerances.

Complex measurements, such as those prescribed using GD&T notation, traditionally require complex go/no-go gauges. These gauges provide information on whether a manufactured part complies with its dimensional specifications. It either passes or it fails. While the application of a go/no-go gauge is quick and simple, what such a gauge does not do is to provide the user with quantitative information on how to correct a manufacturing process that is about to produce failed parts because of, for example, tool wear or temperature drift. Using go/no-gauges is therefore like driving down the highway with the eyes closed. Yes, you do know when you have crashed, but it would be infinitely better to have earlier feedback so you can correct your route and avoid the crash altogether.

Other measurements that involve a complex datum structure are often not possible with either of these conventional methods.

A CMM machine overcomes these limitations by automatically measuring a large number of data points representing the contour of the part to be measured. From that point cloud, even complex GD&T measurements are made possible using numerical techniques. Measurement results can be stored automatically, therefore ensuring data integrity throughout.

Ultimately, a coordinate measuring machine automatically performs the important quality control function and reduces cost by eliminating labour-intensive inspection tasks and keeping a manufacturing process on track through the provision of quantitative feedback data, thus avoiding scrap.

The sensing element of a CMM has traditionally been in the form of a touch probe. Touch probes have been used for decades and provide good quality data, albeit at a cost of slow measurement speed.

In recent years, optical sensors have been used on CMM machines. Depending on the technology, these can have measurement resolutions of tens of micrometres down to nanometres. Their advantage lies in the speed of measurement, when compared to touch probes, and the fact that they do not touch the surface of the part they are measuring.

The throughput required for mass-produced precision components can often only be achieved with the speed and efficiency of an optical coordinate measuring machine. For fragile parts or delicate finishes, such as precision bearings, this is a crucial advantage, as a touch probe can damage these surfaces and require rework or scrapping of a part.

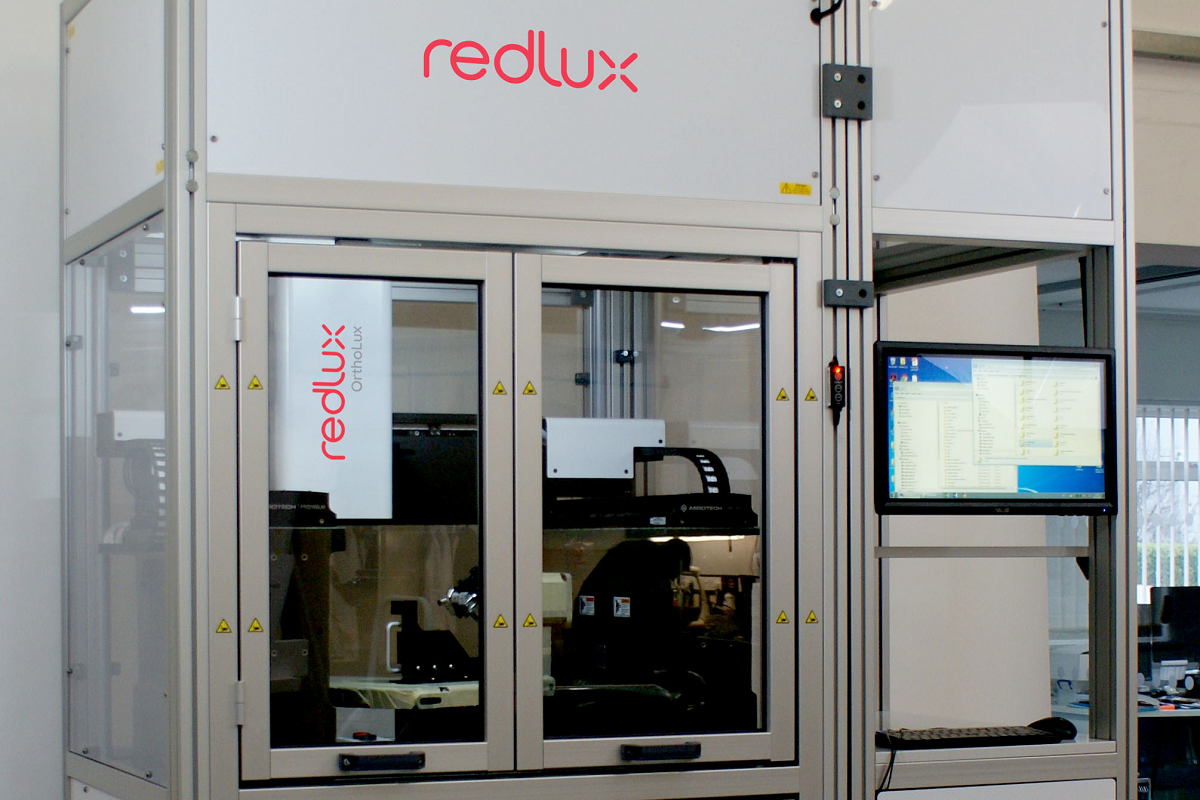

In the image above, an OmniLux 4AB optical CMM measures the bearing surface of an artificial hip joint. This non-contact measurement ensures that the highly polished component remains free from scratches during the inspection process.

Most coordinate measuring machines you will come across use the bridge style configuration. The probe is mounted on a vertical axis (Z). This vertical axis sits on a horizontal axis (X) mounted to a bridge. The bridge itself moves forward and backward (Y). The bridge provides support on both sides. The bridge design is therefore very rigid and can provide high accuracy.

The cantilever coordinate measurement machine does away with one of the bridge supports, thus saving cost and increasing the access envelope for an operator or a robot. Designs are typically smaller than bridge-style machines, as errors increase with the length of the cantilever. They are suited for measuring smaller parts.

As the name suggests, portable measurement arm CMMs are coordinate measuring machines that can be moved around the shop floor. Instead of bringing a component to the CMM, the CMM can be brought to where the component needs to be measured. They typically consist of a 6 or 7 axis system, similar to a robot arm, with a probe at its end. They are not motorised, so require an operator to move the probe around the inspection area. This lack of motorisation means that they are a lower cost option compared to above designs. They are generally less accurate than the bridge or cantilever style machines above.

On bridge and cantilever style CMMs, additional rotary axes are often being used to increase access to the part being measured. This is particularly true for those CMMs fitted with optical sensors because optical sensors have one main measurement direction. Measuring in a different direction requires either the part or the sensor to be rotated. The video below shows an artificial knee joint in an optical coordinate measuring machine, whereby the knee is rotated to provide access to all required features.

For more information on the range of OmniLux optical Coordinate Measuring Machines, please click here:

We’re helping organisations all over the world reap the benefits of world-leading metrology. Speak to our experts.